When Siegfried met Wilfred: A Strange Meeting

- Kieran McGuigan

- Mar 18, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 30, 2021

Kieran McGuigan writes on one of the great encounters in English Literature

Chance brought Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen together in August 1917 at Craiglockhart War Hospital. The influence of this meeting proved of lasting significance in the development of modern English poetry. Biographers report that Sassoon and Owen met in person between 15 to 19 August 1917. Craiglockhart, located in the south-western suburbs of Edinburgh, was occupied during the war by the British Army to house soldiers suffering from what was then known as "shell-shock" but what we would now term post-traumatic stress disorder. Prior to their meeting in Craiglockhart, these two officer-poets had travelled widely dissimilar paths leading them to this strange meeting.

Before the war, Sassoon lived the life of a Kentish, country-gentleman, writing poetry and hunting. Owen, on the other hand, had lived an itinerant life, jumping from roles as a lay assistant to Reverend Herbert Wigan of Dunsden, to a school teacher in Shrewsbury, followed by a year-long stint in France at a boarding school in Bordeaux. Like Sassoon, Owen’s constant star was poetry. A leading authority on the life of Owen, Dominic Hibberd, comments that ‘despite the conflict, however, evangelical habits persisted into his method of reading literature’.

A year into the Great War, both men enrolled as officers, and almost immediately assumed front-line duties. By late 1915, Sassoon had earned a reputation among his men as ‘Mad-Jack’, due to his brave, some would say foolhardy, exploits. He was awarded the Military Cross for rescuing a wounded lance-corporal under heavy machine gun fire and artillery bombardment; later, he was awarded the Victoria Cross for single-handedly capturing a German trench. In November 1915, it is said Sassoon met Robert Graves, an aspiring fellow writer and poet. LIke Sassoon and Owen, Graves was destined to become one of the major Anglo-Modernist poets and writers of the 20th century.

What changed Sassoon irrevocably was witnessing the death of his close-friend David Thomas. Contemporary accounts recount how Sassoon’s brave exploits teetered on the suicidal; his early apathy and disdain for the brutalities of trench warfare now began to manifest itself in outrage. On the night of the 14th April 1917, Sassoon recorded in his diary that he was ‘fully expecting to get killed on Monday morning’. The next day, apparently after making himself an easy target for German snipers, he stuck his head above the parapet of a trench and was struck in the temple. Somehow, he survived and was sent back to England.

During his convalescence, Sasson met H.W. Massingam, editor of The Nation, along with the eminent philosopher Bertrand Russell. Both men encouraged Sasson, the highly decorated soldier, to make a public statement denouncing the war. In his autobiography, Sassoon declared that during this period he threw his Military Cross into the River Mersey, as a way of expressing his disgust for the war and for the military authorities who were prolonging it. He now felt it was time that he went public. In July 1917, he wrote ‘A Soldiers Declaration’ and sent it to the commanding officers of the 3rd Battalion, of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He apologised but he outlined his opposition to the war and stated that he would not be returning to the frontline. He fully expected to be court martialled; he wrote to Robert Graves, stating ‘(I am) fully aware of what I am letting myself in for’.

In contrast to Sassoon, Owen had been on the frontline at the Battle of the Somme since January 1917. He had been engaged in fierce contintual fighting up until May, when he began to show signs of psychological trauma due to the horrors he had witnessed. As a result of his worsening condition, he was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in June 1917. On 31st July, as the British army began the first offensive in the Battle of Passchendaele, Sassoon’s ‘A Soldier's Declaration’ was published in The Times, and read aloud in Parliament. However, instead of being court martialled as he expected, Sassoon was declared 'mad' by a British Army medical board, who wished to avoid the controversial publicity that would surround a military tribunal in which the defendant was a decorated war hero. Thus it was, in July 1917, Sassoon was packed off to Craiglockhart War Hospital and out of harm's way. The stage was set for one of the great encounters in the whole English literary history.

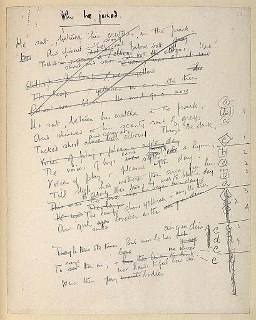

During their formative discussions, Sassoon condemned Owen’s early lyrics as being ‘over-luscious writing in his immature pieces’. Like a lot of Georgian prose and poetry, Owen’s early poems and letters are full of self-conscious youthful and romantic sentiments. He muses about nature and the English landscape in language rife with late Victorian sumptuousness, mimicking the melodious chimes of Shelley, and the esoteric symbolism of Keats. Until his encounter with Sassoon, there is little evidence of Owen’s attempts to write about his own first-hand experience of the horrors of the western front. Hung up on Romantic sentiments about the sanctity of poetry, he believed that his own poems should not tackle the grim obscenity of modern-warfare. Sassoon, however, quickly put pay to that; he encouraged Owen to write unfinchingly about what he had experienced in France in order to bring home to the British public what the soldiers were going through.

From the correspondence between Sassoon and Graves in October 1917, we can see how these older more established figures reacted to the extraordinary work of the younger poet.

Graves to Edward Marsh dated 29 December 1917

I have found a new poet for you, just discovered one, Wilfred Owen…the real thing; when we've educated him a trifle more. R.N & S.S and myself are doing it.

Graves to Owen, dated December 1917

... you must help S.S and R.N and R.G to revolutionise English poetry-So outlive this War.

Graves to Marsh, dated January 1918

I send you a few poems of Owen I can find; not his best but they show his powers & deficiencies-Too Sassoonish in places; Sassoon is to him a god of the highest rank (…) Isn't it good that Bob Nicholas & Sass get on so well (…) Beginning to understand infinitely more clearly what Georgian Poetry means, and what is going on to mean by God's grace.

By the close of 1917, Owen himself wrote in a letter to his mother, 'They believe in me these Georgian's (…) I am held peer by the Georgian's: I am a poet's poet. I am started. The tugs have left me; I feel the great swelling of the ocean sea taking my galleon'. Tragically, Owen's sense of his own vocation as a poet was short-lived. On 4th November 1918, one week before the Armistice, he was killed during an assault on the Sambre Canal, along the Western Front. Owen never lived to witness his first books of poetry published in 1920, a single volume edited by his friend and mentor Siegfried Sassoon.

Thus, from this strange meeting, Owen was transformed - both as a poet and as a man. From being a late-Victorian romantic mimicking Keats, he matured into the greatest war-poet of the 20th century. English poetry would never be the same again. Also, the way in which future generations regard warfare would never be the same again.

This is a great link: Poetry, Shell-Shock and Siegfried Sassoon:

Comments